ARMENIAN APRICOT- SYMBOL OF NATIONALITY & VICTORY

The apricot is an important fruit for Armenians. It is almost sacred; it is even revered.

Historically, in the third century BC, Akkadians called the apricot “armanu” (meaning Armenian), and Armenia “Armani”. One of the ancient peoples of Mesopotamia, Arameans, called the apricot tree “Khazura Armenia” (the tree of the Armenian apple). After fighting Armenian King Tigranes the Great in the first century BC, Roman general Lucullus took several apricot saplings from Armenia to Rome. The Romans planted those saplings in their city and called the fruit the “Armenian plum” (Prunus Armeniaca).

Historically, in the third century BC, Akkadians called the apricot “armanu” (meaning Armenian), and Armenia “Armani”. One of the ancient peoples of Mesopotamia, Arameans, called the apricot tree “Khazura Armenia” (the tree of the Armenian apple). After fighting Armenian King Tigranes the Great in the first century BC, Roman general Lucullus took several apricot saplings from Armenia to Rome. The Romans planted those saplings in their city and called the fruit the “Armenian plum” (Prunus Armeniaca).

The plant spread all over Europe from Rome. For example, De Poerderlé, writing in the 18th century, asserted, “Cet arbre tire son nom de l’Arménie, province d’Asie, d’où il est originaire et d’où il fut porté en Europe …” (“this tree takes its name from Armenia, province of Asia, where it is native, and whence it was brought to Europe …”). An archaeological excavation at Garni in Armenia found apricot seeds in an Eneolithic era site.

The scientific name armeniaca was first used by Gaspard Bauhin in his Pinax Theatri Botanici (page 442), referring to the species as Mala armeniaca “Armenian apple”. It is sometimes stated that this came from Pliny the Elder, but it was not used by Pliny. Linnaeus took up Bauhin’s epithet in the first edition of his Species Plantarum in 1753.

The name apricot is probably derived from a tree mentioned as praecocia by Pliny. Pliny says “We give the name of apples (mala) … to peaches (persica) and pomegranates (granata) …” Later in the same section he states “The Asiatic peach ripens at the end of autumn, though an early variety (praecocia) ripens in summer – these were discovered within the last thirty years …”.

In fact, evidence of apricots in Armenia far predates Pliny. According to CWR, the ongoing project to document and preserve Armenia’s native wild crops, the Chinese cite references to apricots in their literature going back 4,000 years. But apricot pits have been excavated near Garni and Yerevan dating back 6,000 years; thus CWR concludes, “We can see the cultivation of apricots in Armenia is 2000 years older than China”.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, a leading botanist in the 18th century, finally decided that this fruit was not a type of plum, but a new species, and called it “Armeniaca vulgaris.” In the 12th century, thanks to Ibn al-Awwam, apricot took an Arabic name: “tufah al Armani” (Armenian apple). Today, in scientific literature, apricot’s Latin name remains “Prunus Armeniaca”.

The same source notes that the apricot tree has been celebrated in Armenian literature since ancient times and that the Armenian word for apricot (tsiran) appears to be of Armenian origin and is found in the Armenian translation of the Bible.

What interests us most of all, of course, is how universally apricots are found on the Armenian table. Virtually every variant of Armenian cuisine includes a litany of apricot recipes. We boil them into jellies, jams, marmalade and compotes. We stew them with lamb or chicken. We steep them in pilafs and stuff them in meats.

The apricot has been the symbol of nationality and victory for Armenians for many centuries. In the middle ages. Armenian kings and knights would go to battle wearing apricot-colored ornaments called “tsirani.” One of the three colors of the tri-color Armenian flag is also the color of the apricot. Every year in July in Armenia, during the harvest of apricots an “apricot festival” is held.

People from different villages and towns bring to the capital of the country apricots from their own gardens in straw baskets, dried apricots, alcoholic beverages made of apricots, and many other foods and drinks made from the richest apricots. People cheer on their cleverness and treat others to their homemade food. This is a national trait – treating others and being happy when others like the food. For one whole day the Armenian land, its waters, and their fruit- the apricot, are being praised and celebrated.

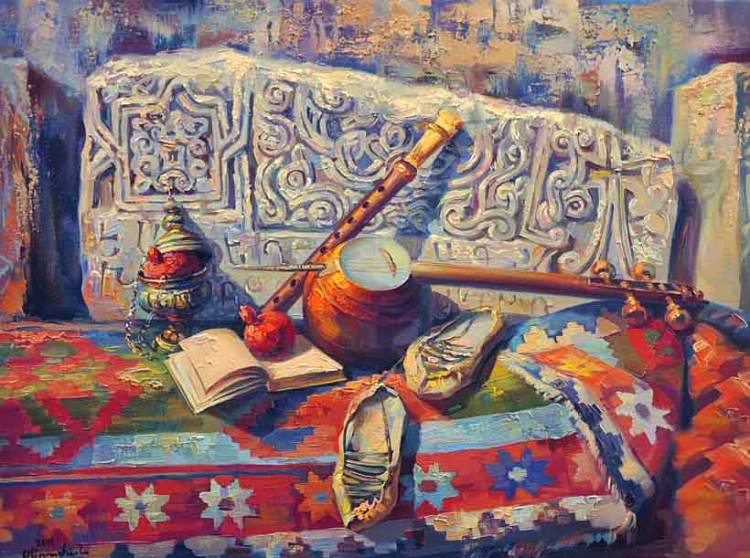

In Armenia, the wood of the apricot tree is used for making wood carvings such as the duduk, which is a popular wind instrument in Armenia and is also called the apricot pipe. Several hand-made souvenirs are also made from the apricot wood.

KHACHKAR

Each culture possesses a certain original element which becomes a symbol of the entire national culture. In Armenia that symbol is considered to be “khachkar”, the so-called cross-stones, in other words- the monuments of Armenia.

Each culture possesses a certain original element which becomes a symbol of the entire national culture. In Armenia that symbol is considered to be “khachkar”, the so-called cross-stones, in other words- the monuments of Armenia.

Khachkar is an art decorative-architectural sculptures based on the ancient national traditions and are made in different shapes.

Khachkars are outdoor steles carved from stone by craftspeople in Armenia and communities in the Armenian Diaspora. They act as a focal point for worship, as memorial stones and as relics facilitating communication between the secular and divine. Khachkars reach 1.5 metres in height, and have an ornamentally carved cross in the middle, resting on the symbol of a sun or wheel of eternity, accompanied by vegetative-geometric motifs, carvings of saints and animals.

Once finished, the Khachkar is erected during a small religious ceremony. After being blessed and anointed, the Khachkar is believed to possess holy powers and can provide help, protection, victory, long life, remembrance and mediation towards salvation of the soul. Among more than 50,000 Khachkars in Armenia, each has its own pattern, and none looks alike. Khachkar craftsmanship is transmitted through families or from master to apprentice, teaching the traditional methods and patterns, while encouraging regional distinctiveness and individual improvisation.

A typical cross-stone is made out of slate of volcanic basalt or tuff. The central symbol of any khachkar was a new-born, growing like a tree or a flower, cross- the symbol of a new eternal life. Under the cross they cut a circle: the circle with the cross on it symbolizing celebration of birth of life, also called sun crosses. Above the cross they usually placed common Armenian faith symbols- an eagle, a lion, a bull and an angel. For Armenians they were four beginnings of the universe- fire, water, earth and air.

The cross is truly ancient and was used by Armenian Pagans long before Christians adopted the cross in the 9th century.

Old Pagan fertility dragon stones (vishapakar) can be seen in Armenia near lakes, rivers and springs, where they represent the Tree of Life and the biblical Garden of Eden including fish-shaped vishapakars that were carved and erected thousands of years before the Christian khachkar stones.

Although the vishapakars evolved into khachkars, the fish tail was retained along with its Tree of Life and Wisdom interpretation. An addition was the equilateral geometry which symbolizes harmony, Sacred Geometry.

Unfortunately, in the past few years, invaders have looted and vandalized many khachkars, destroying thousands of these stone treasures.

The stone-cutters who made khachkars are called varpets (masters). Their art is alive and is in demand even now. Khachkars keep the spirit of Armenian people. It is quite natural that the art of Armenian khachkar is compared only with another magnificent phenomenon of the Armenian medieval art, that of Armenian miniature.

The biggest cemetery with ancient khachkars in Armenia is near the settlement of Noraduz. A millennium of Armenian history is embodied in the khachkars over there.

In 2010 Armenian cross-stone art was included in UNESCO intangible cultural heritage list. In every culture there is a distinctive element which is not found anywhere else, and which has become a symbol of the entire national culture.

MOUNT ARARAT- A PIECE OF CREATION

Mount Ararat (piece of gods or piece of creation) is the most important geographic symbol of Armenian identity having the same significant relationship to the Armenians as Mount Olympus to the ancient Greeks.

Mount Ararat, being sacred and an outstanding symbol of political existence and just an integral part of Armenian national life represents the fatherland to Armenians around the world.

Armenia occupied the rugged mountain terrain located between the Caucasus Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea. In the heart of the Armenian highlands is Mount Ararat, mentioned in the book of Genesis as the place where the Ark of Noah rested after the Great Flood. According to the legend, the Garden of Eden was located on a picturesque plateau around Mount Ararat.

The mountain has twin peaks known as “Great Masis” and “Little Masis”. Their bases are confluent at a height of 8,800 feet; and summits are about seven miles apart. The higher Great Ararat which attains a height of 16,916 feet (5,165m) is a huge broad-shouldered mass, more of a dome than a cone. The lower little Ararat at 12,840 feet (3,896m) is an elegant cone or pyramid, rising with a steep, smooth regular side into a comparatively sharp peak.

As it is mentioned in many researches, the first god in Armenia was one of the language’s first sounds, “AR” (meaning sun or light). As the source of life, the sun became equated with power and the supreme god. The Armenian mountain Ararat is mentioned as early as ca. 6000 BC in the Sumerian epoch poem Gilgamesh, as the land of the mountains where the gods live. However, the word Ararat can be divided into three words: AR-AR-AT. AR-AR is the plural form or all encompassing god; “AT” being an archaic version of the Armenian word “hat”, which means “a piece of”. Thus Ararat meant “a piece of gods, or a piece of creation”.

The letter combination “Ar” describes one of the most ancient Armenian designations. As such the most important and often used emotional Armenian words until today start with these two letters (e.g. Arun= Blood, Arev= Sun, Aravot=Morning, Arach=first, etc.) hence the name People of AR.

The worship of Armenian sun deity (AR) goes way back to pre-recorded history. The ancient Armenian Wheel of Eternity a symbol attesting to the worship.

ARMENIAN SYMBOL OF SUN ON THE GROUND

There are different Armenian ancient sun symbols but not many people know that the Armenians also have the sun symbol on the ground. That is the Armenian Tonir. From ancient times till now the Tonir was worshiped by the Armenians like other sun symbols and it is known as a symbol of Sun in the ground.

Ancient Armenians made tonirs in resemblance with the setting sun “going into the ground” (Sun being the main deity).

The underground clay Tonir is one of the first tools of Armenian cuisine, as an o

ven and as a thermal treatment tool. Everything that is made in pots and in tonirs has Armenian origin, but only Armenians had underground tonirs. It isn’t accidentally that the secret of the special taste of Armenian dishes /BBQ-Xorovats, Fish, Gata, Lavash/ cooked in a tonir is hidden there, where the food is made.

Other nations have borrowed the Tonir from Armenians and are using it nowadays, but only Armenians are aware of the ritual meaning of the Tonir. Armenians were already using the tonir thousand years ago. In the stage of sun worshipping, the Tonir is considered to be the symbol of sun on the earth. Pagan Armenians have resembled tonir with sunset. Every time Armenian women are baking bread or preparing food, they bent down before the Tonir, which also meant worship for deity.

Unlike other people, who also may have something like the Tonir to bake bread, the Armenian Tonir has been used for different purposes. The Armenians cooked meals in the Tonir, they used the Tonir to heat the house, moreover, it was perfect for medical purposes, for example, to warm and cure the sick and afficted.

Obviously, the traditional tonir has a great medicinal effect. In ancient times it has been situated in the center of the house, which was symbolizing the permanent providing of sun heat in the house. They were putting “kursi” on the Tonir, were covering it with a carpet and they were putting their feet under the ”kursi” in cold days. The Tonir had also a non bacterial effect, as they have used the cow’s dung, as a fuel, which has been famous for its medicinal traits since ancient times.

Formerly, the Tonir hasn’t only an important meaning in Armenian cuisine, but also in lifestyle. In traditional families the Tonir has always been identified with “home”. It is not a secret that in ancient times Armenian families have lived under one single roof, where, as a rule, in the center of the large room was a Tonir. It was the base of the Armenian family, where they were not only baking bread and preparing food, but also preceded Armenian family’s life in good, old times around it. They were marrying, even healing near the Tonir. The members of the family were gathering around it at dinner time, or during the parties and the rest.

In the Armenian Highlands they have baked bread 3-2 millenniums before the birth of Christ. That confirms the clay ovens (tonir) and the relics of bread, which have been discovered in a variety of old places. During the excavations of Artashat city, Armenia, there have been discovered tonirs of that same period.

Though the rules of lifestyle have changed in time, the custom of baking Lavash, bread, gata and making a lot of food in a Tonir has remained unbreakable.

Smoke of tonir is continuing to stay the symbol of peace, unification and strengthening of Armenian family and home.

Since 2012 “Tonraton” – the Food Festival has been held in Armenia. On August 11, for the Navasard holiday (the old Armenian “New Year”, which was dedicated to Armenian pagan gods), featuring dishes cooked in this forefather of the modern oven.