TOURINFO-April 17, 2021-New York Times

TOURINFO-April 17, 2021-New York Times

A scholar, a university leader, and a believer in libraries, he almost single-handedly rescued a grand but broken one in a time of municipal austerity.

A scholar, a university leader, and a believer in libraries, he almost single-handedly rescued a grand but broken one in a time of municipal austerity.

April 16, 2021

Vartan Gregorian, the ebullient Armenian immigrant who climbed to pinnacles of academic and philanthropic achievement but took a detour in the 1980s to restore a fading New York Public Library to its place at the heart of American intellectual life, died on Thursday in Manhattan. He was 87.

The death, at a hospital, was confirmed by his son Dareh Gregorian. No cause was given.

Dr. Gregorian liked to tell the story of “the most painful experience of my entire life.” It happened in 1980 when he was provost of the University of Pennsylvania, its top academic official. Powerful trustees told him that he was a shoo-in to replace the outgoing president. He was so sure of the post that he withdrew his name from consideration as chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley.

He heard the bad news on his car radio. The Penn trustees had chosen another academic star. The next day, he resigned. The outgoing president tried to dissuade him, but it was no use.

“I told him that I could cope with rejection, but not insult and humiliation,” Dr. Gregorian said in a memoir, “The Road to Home: My Life and Times” (2003).

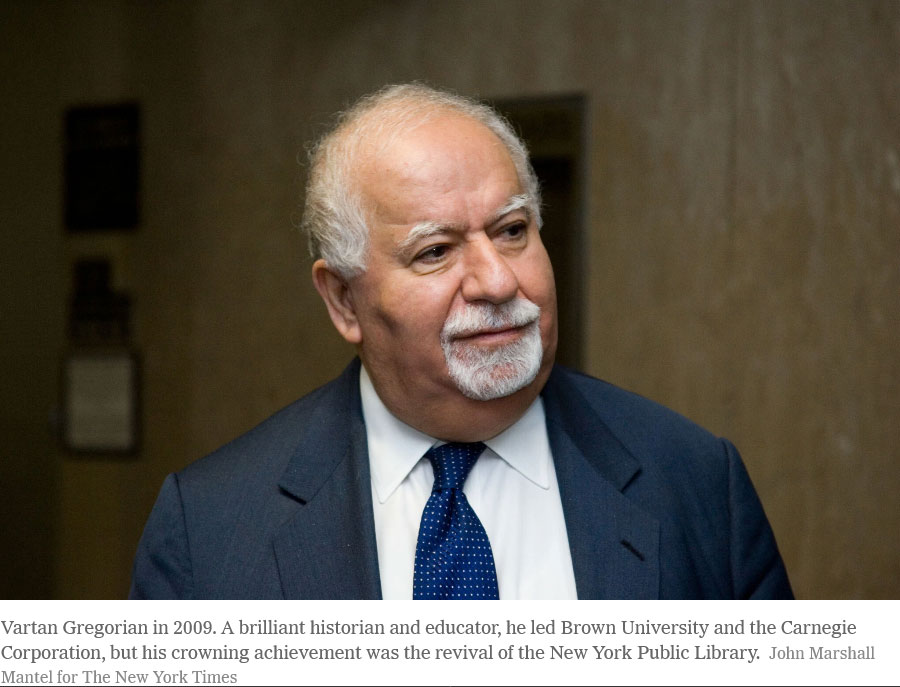

Indeed, Dr. Gregorian was a fighter: proud, shrewd, charming, a brilliant historian and educator who rose from humble origins to speak seven languages, win sheaves of honors, and be offered the presidencies of Columbia University and the Universities of Michigan and Miami. He accepted the presidency of Brown University (1989-1997), transforming it into one of the Ivy League’s hottest schools, and since then had been president of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, a major benefactor of education.

But he was best known for resurrecting the New York Public Library from a fiscal and moral crisis. It was a radical, midcareer change from the pastoral academic realm, and a risky plunge into the high-profile social and political wars of New York City, where the budget-cutting knives were out after decades of profligacy, neglect, and a brush with municipal bankruptcy in the 1970s.

By 1981, when the feelers went out to Dr. Gregorian, the library — the main research edifice at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue and 83 branches in Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island — was broke, a decaying Dickensian repository of 7.7 million books (the world’s sixth-largest collection), many of them rare and valuable, gathering dust and crumbling on 88 linear miles of stacks.

By 1981, when the feelers went out to Dr. Gregorian, the library — the main research edifice at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue and 83 branches in Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island — was broke, a decaying Dickensian repository of 7.7 million books (the world’s sixth-largest collection), many of them rare and valuable, gathering dust and crumbling on 88 linear miles of stacks.

The underpaid, overworked staff was demoralized. The beautiful Gottesman Exhibition Hall had been partitioned into cubicles for personnel and accounting. Tarnished chandeliers and lighting fixtures were missing bulbs. In the trustees’ board room, threadbare curtains fell apart at the touch. Outside, the imperious marble lions, Patience and Fortitude, and the portals they guarded were dirt-streaked. Bryant Park in the back was infested with drug dealers and pimps and unsafe after dark.

But the main problems were not even visible. The library faced a $50 million deficit and had no political clout. Its constituencies were scholars, children, and citizens who liked to read. The city had cut back so hard that the main branch was closed on Thursdays, and some branches were open only eight hours a week.

To Dr. Gregorian, the challenge was irresistible. The library was, like him, a victim of insult and humiliation. The problem, as he saw it, was that the institution, headquartered in the magnificent Carrère and Hastings Beaux-Arts pile dedicated by President William Howard Taft in 1911, had come to be seen by New York City’s leaders, and even its citizens, as a dispensable frivolity.

He seemed a dubious savior: a short, pudgy scholar who had spent his entire professional life in academic circles. On the day he met the board, he was a half-hour late, and the trustees were talking about selling prized collections, cutting hours of service, and closing some branches. He asked only for the time and offered in return a new vision.

“The New York Public Library is a New York and national treasure,” he said. “The branch libraries have made lives and saved lives. The New York Public Library is not a luxury. It is an integral part of New York’s social fabric, its culture, its institutions, its media, and its scholarly, artistic, and ethnic communities. It deserves the city’s respect, appreciation, and support. No, the library is not a cost center! It is an investment in the city’s past and future!”

Friends in High Places

His personality was so engaging, his fire for restoring the library so compelling, that the board endorsed him unanimously as its president and chief executive. So long as he succeeded, he would be given time. He needed money, too, but he was an experienced university fund-raiser.

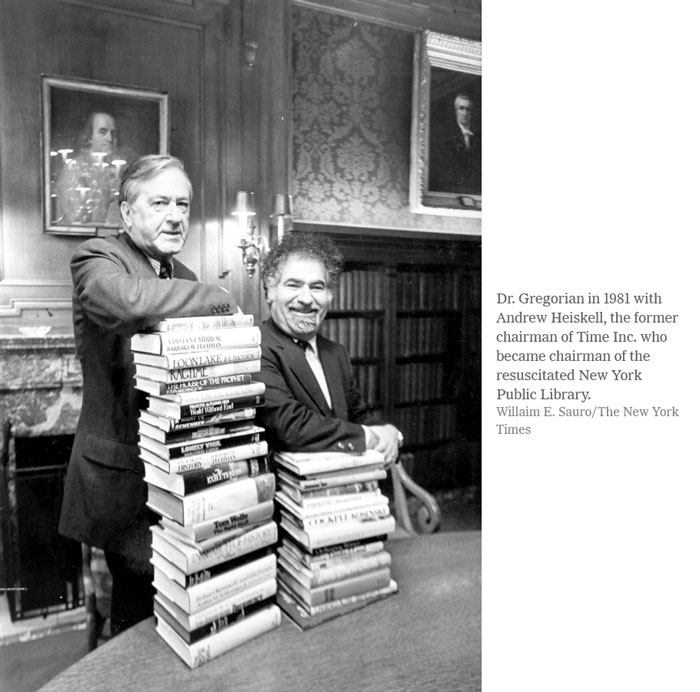

More than money, he needed allies. He found them in Andrew Heiskell, the incoming library chairman, who had just retired as chairman and chief executive of Time Inc.; Richard B. Salomon, the library’s vice chairman, who had been chairman since 1977; and Brooke Astor, the widow of Vincent Astor and doyenne of society who was presiding over bequests of $195 million to charitable causes.

Dr. Gregorian wrote: “Richard Salomon paved the way for individual giving and business and Jewish philanthropy; Andrew Heiskell went after individuals and major corporations, his former pals; Mrs. Astor opened the doors of New York society and its philanthropy. They helped me make the case for the New York Public Library, making it a civic project that was both honorable and glamorous.”

Mrs. Astor gave a black-tie party to introduce Dr. Gregorian and his wife, Clare Gregorian, to New York society. Weeks earlier, she had given a party for President Ronald Reagan and the first lady, Nancy Reagan. When Dr. Gregorian voiced surprise that the guestlist for both dinners was substantially the same, Mrs. Astor told him, “The president of the New York Public Library is an important citizen of New York and the nation.”

“Literary Lions” dinners at $1,000 a plate were soon underway, attended by the likes of Isaac Bashevis Singer and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Dr. Gregorian met corporate and foundation leaders to drum up support and spread goodwill. He gave and attended dinner parties, and with Mrs. Astor, who made the library her top philanthropic priority, organized charity balls and other functions.

In the news regularly with his appeals, Dr. Gregorian often sounded like a voice of conscience. He called the library “a sacred place,” telling The New Yorker: “Think of a lone person in one of our reading rooms, who has just read a book, a single book that has perhaps not been read in 20 years by another living soul, and from that reading comes an invention of incalculable importance to the human race. It makes a man tremble.”

In the news regularly with his appeals, Dr. Gregorian often sounded like a voice of conscience. He called the library “a sacred place,” telling The New Yorker: “Think of a lone person in one of our reading rooms, who has just read a book, a single book that has perhaps not been read in 20 years by another living soul, and from that reading comes an invention of incalculable importance to the human race. It makes a man tremble.”

Results began to show. The main library and many branches restored days of service. The card catalog was computerized. Temperature and humidity controls were installed, public rooms were air-conditioned, facades were cleaned, and a $45 million renovation was launched. Partitions and cubicles were removed, marble walls were restored, and carved wooden ceilings were refinished. Scores of projects began. One was a cleaning of the books and stacks, undusted for 75 years.

Tides of tourists and visitors returned. Exhibitions, lectures, concerts, and other cultural events made the main library a beehive of intellectual life, day and night. Afternoon and evening activities in Bryant Park drew crowds that chased the ne’er do wells. Out front, Patience and Fortitude were bathed, and people of all ages lounged on the broad steps to bask in the sunshine.

Dr. Gregorian campaigned as if running for election. Mayor Edward I. Koch, who knew a good thing when he saw one, climbed on the bandwagon, and former Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. said of Dr. Gregorian: “He reminded us that libraries were engines of hope that move people into the middle class and to worlds beyond themselves.”

He was masterful in dealing with the City Council and the Board of Estimate, which in those days held the purse strings. On the job less than two years, he told the council’s Finance Committee that it was demeaning for him to annually defend the library’s right to exist. He said he would no longer come hat-in-hand and would only present the library’s case for a fair share of the money.

By the end of his tenure, in 1989, Dr. Gregorian had raised $327 million in public and private funds for the library, placing it on a firm footing.

“What he did was put the library in the spotlight,” Mr. Heiskell told The New Yorker. “He had to change the mood of the city for the library, of the people in the city for the library, and of the people in the library for the library.

“In essence, he had to change the future.”

Armenians in Iran

Armenians in Iran

Vartan Gregorian was born on April 8, 1934, in the Armenian quarter of Tabriz, in northwest Iran, to Samuel and Shooshanik (Mirzaian) Gregorian. His father was an accountant for the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Vartan’s older brother, Aram, died in infancy, and his mother died of pneumonia when he was 6. His father was drafted in World War II and later became an often-unemployed office worker.

Vartan and his younger sister, Ojik, were raised by their maternal grandmother, Voski Mirzaian, an illiterate but gracious storyteller whose allegorical fables instilled in the children lessons in morality: about telling the truth, possessing integrity, and the dignity to be found in stoicism and good deeds.

“She was my hero,” Dr. Gregorian said in an interview for this obituary in 2019. “I learned more about the character from her than from anybody I ever met or any book I ever read.”

Vartan was a voracious reader and spent much time in the extensive library of his Armenian Church, where he had a part-time job in the stacks. “It was heaven,” he said. “There were translations of all the Western classics, and I read Russian literature, so I became familiar with Shakespeare, Lord Byron, Tolstoy, Dumas, and Victor Hugo.”

Languages came to him easily. “We had Armenian at home, Russian at school, and we grew up with Turkish and Persian,” he said. He recalled that after his father remarried, he could not tolerate his stepmother and ran away from home at 15.

He landed in Beirut, Lebanon, with a teacher’s letter of introduction to the Collège Arménien, a lycée founded in 1928 to educate Armenian refugees. Simon Vratzian, the Armenian Republic’s last prime minister, was the school’s director. He enrolled the boy and became his mentor. Vartan learned French, Arabic, and smatterings of English before graduating in 1955 with honors.

In 1956, he won a scholarship to Stanford University. Despite starting with shaky English, he became fluent and, majoring in history and humanities, earned a bachelor’s degree with honors in two years.

In 1960, he married Clare Russell, a fellow student at Stanford. In addition to Dareh, they had two more sons, Vahé and Raffi, all of whom survive Dr. Gregorian, along with his sister and five grandchildren. He lived in Midtown Manhattan.

A Ford Foundation fellowship took Dr. Gregorian to England, France, Lebanon, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and India. He earned a dual doctorate in history and humanities from Stanford in 1964. He taught European and Middle Eastern history at San Francisco State College, U.C.L.A., and the University of Texas before joining the University of Pennsylvania in 1972.

At Penn, he was a professor of Armenian and South Asian history for eight years, the school’s first dean of what is now the College of Arts and Sciences, from 1974 to 1978, and then provost until his departure in 1980 after being passed over for the presidency.

After his acclaimed work to save the New York Public Library, Dr. Gregorian, as the president of Brown University, led a five-year campaign there that raised $534 million, the most ambitious in Brown’s history. He raised the endowment to $1 billion from $400 million, doubled undergraduate scholarships, hired 270 new faculty members, endowed 90 professorships, and built a student residence that bears his name. In his last year, there were 15,000 applicants for 1,482 places in the freshman class.

It was in 1997 that Dr. Gregorian assumed the presidency of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the foundation created by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to promote education and peace. After decades as a supplicant, raising $1 billion for universities and libraries, he became a benefactor, starting with an endowment of $1.5 billion that grew to $3.5 billion over his tenure.

His grants strengthened education, international security, democratic institutions, and global development. Domestically, he emphasized reforms in teacher training and liberal arts education; abroad, he stressed scholarships for social sciences and humanities.

Dr. Gregorian also advised philanthropists, including Bill and Melinda Gates, Walter H. Annenberg, and officials of the J. Paul Getty Trust. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded him the National Humanities Medal, and in 2004 President George W. Bush conferred on him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Besides his memoir, he wrote, “The Emergence of Modern Afghanistan: Politics of Reform and Modernization, 1880-1946” (1969); “Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith” (2004), and many articles on history and global affairs.

Besides his memoir, he wrote, “The Emergence of Modern Afghanistan: Politics of Reform and Modernization, 1880-1946” (1969); “Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith” (2004), and many articles on history and global affairs.

Dr. Gregorian, who often recalled the kindness of strangers, said that after landing in New York in 1956 to start life in America, he lost his plane ticket to San Francisco. He was due to register the next day at Stanford. His future seemed to hang in the balance. In faltering English, he poured out his desperation to an airport ticket agent.

The man hesitated, saying something about regulations. Then he softened.

“I have never done what I am about to do,” the agent said. He stamped the young man’s empty ticket envelope and told him to stay on the plane — a four-stop, 14-hour flight — to avoid discovery.

“I never forgot that man,” Dr. Gregorian said in the 2019 interview. “He gave me my future. For years I wanted to thank him but couldn’t find him. I told the story in my book to thank him — and now my conscience is clear.”