TOURINFO– BBC’s Ismail Einashe has traveled to Ethiopia to find out about the Armenian community.

His search for the last Armenians of Ethiopia began in Piassa, the bustling commercial center of the old part of the capital, Addis Ababa. He visits the St George Armenian Apostolic Holy Church built in the 1930s.

“The community reached its zenith in the 1960s when it numbered 1,200. Despite their small numbers they had a crucial role in ushering Ethiopia into the modern world – from helping to develop the distinctive Ethiopian jazz style to working as tailors, doctors, business people and serving in the imperial court,” Ismail Einashe wrote.

“The community reached its zenith in the 1960s when it numbered 1,200. Despite their small numbers they had a crucial role in ushering Ethiopia into the modern world – from helping to develop the distinctive Ethiopian jazz style to working as tailors, doctors, business people and serving in the imperial court,” Ismail Einashe wrote.

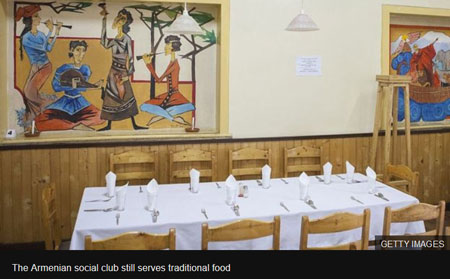

According to the BBC, there is also an Armenian social club, which has a restaurant that reminds people of the taste of home.

Read More….

In our series of letters from African journalists, Ismail Einashe takes a trip to Ethiopia to find out about a lost community.

In our series of letters from African journalists, Ismail Einashe takes a trip to Ethiopia to find out about a lost community.

My search for the last Armenians of Ethiopia began in Piassa, the bustling commercial center of the old part of the capital, Addis Ababa.

My search for the last Armenians of Ethiopia began in Piassa, the bustling commercial center of the old part of the capital, Addis Ababa.

On previous visits to the city, I had always been intrigued by the snippets I had heard about the community and its history.

There had long been a connection between Ethiopia and Armenia through the Orthodox Church. But this developed beyond priests, to bring in diplomats and traders.

In the 19th Century, a handful of Armenians played a vital role in the court of Emperor Menelik II.

And later, in the early 20th Century, a community settled that went on to have an economic and cultural impact in the country.

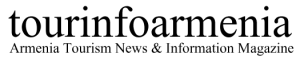

On a sticky afternoon, I stood outside the gates of the exquisite St George Armenian Apostolic Holy Church that was built in the 1930s.

On a sticky afternoon, I stood outside the gates of the exquisite St George Armenian Apostolic Holy Church that was built in the 1930s.

It looked closed but I called out “Selam” – “hello” in Amharic.

A confused-looking elderly security guard came out and after I explained that I wanted to look around, he went to fetch Simon, the Armenian-Ethiopian caretaker.

The quiet, dignified man came out and told me that they do not get many visitors.

Haile Selassie’s influence

The church is rarely open, as there is no priest these days, and the community, of no more than 100, is mostly elderly.

Inside the church, the altar is ornately decorated and red Persian rugs cover the floor.

This was the heart of the community that began to grow in numbers during the rule of Haile Selassie who, as Ras Tafari, became prince regent of Ethiopia in 1916 and Emperor from 1930 to 1974.

Under his leadership, Ethiopia began to rapidly modernize and Armenian courtiers, businesspersons and traders played an important role in this transition.

In 1924, Ras Tafari visited the Armenian monastery in Jerusalem, where he met a group of 40 children who had been orphaned by the mass killing of Armenians by Ottoman Turks during World War One.

Moved by their plight, he asked the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem if he could take them to Ethiopia and look after them there.

The 40 orphans, or Arba lijoch in Amharic, were all trained in music and went on to form the imperial brass band of Ethiopia.

An Armenian, Kevork Nalbandian, who composed the imperial anthem, led them.

An Armenian, Kevork Nalbandian, who composed the imperial anthem, led them.

The community reached its zenith in the 1960s when it numbered 1,200.

Despite their small numbers they had a crucial role in ushering Ethiopia into the modern world – from helping to develop the distinctive Ethiopian jazz style to working as tailors, doctors, business people and serving in the imperial court.

Emperor’s overthrow

But as the Armenian community was tied to the imperial history of the country, once the emperor fell the community declined.

Haile Selassie was overthrown in 1974 by the Marxist Derg junta, which went on to seize businesses and property, including that of the Armenians.

Their numbers tumbled as many fled to North America and Europe.

But a few stayed and some married within the local community, creating a unique blend of Armenian and Ethiopian cultures.

They can still be seen in the church for special religious celebrations.

But there is also the Armenian social club, which has a restaurant that reminds people of the taste of home.

But there is also the Armenian social club, which has a restaurant that reminds people of the taste of home.

Simon, the church caretaker, told me that I should go.

Delicious food

It was a Tuesday night and, apart from my friend and myself, there was a group of three Armenian-Ethiopian women who were delighted to see strangers in the restaurant.

They admitted that the community was not what it used to be. But the social club remained as a way to keep it alive.

That night, as I tucked into delicious and sumptuous börek and lyulya kebabs, I felt I was tasting the history of the Armenians in Ethiopia.